Upon arrival at New Delhi’s Indira Gandhi International Airport little spoke of the U-17 World Cup, but across the Indian capital, a vast megapolis of centralized political power, historical monuments and poisonous smog one single billboard popped up in every metro station, screaming in Hindi ‘Football’s Power of Youth,’ with Prime Minister Narendra Modi striking a stern pose, arms folded. The sexagenarian was about to do a player presentation and say ‘I am David Luiz and I am a central defender.’

By Samindra Kunti

The beautiful game became a part of the PM’s nation-building exercise. Backed by nationalistic rhetoric and the promise to rejuvenate India, Modi swept to power in 2014 with a historic mandate, but in the second quarter of 2017 amid economic mismanagement and frail growth rates he faced a political crisis. Within his conservative Bharatiya Janata Party, Modi was on the defensive. For a moment, football was to take him on the offensive again.

On a wearing and hot afternoon tuk-tuks, yellow cabs and Ubers were wrestling for every inch of Delhi’s tarmac in the vicinity of the Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium, a monolithic arena of crosshatched steel beams. Long lines of school boys, clad in 26,750 blue India T-shirts, were shepherded towards the stadium. Shortly before kick-off, Modi arrived with his immense security cordon and the sullen Special Protection Group in tow. His attention to sartorial detail was, as ever, immaculate: under a grey Nehru jacket he wore a pearl-white kurta.

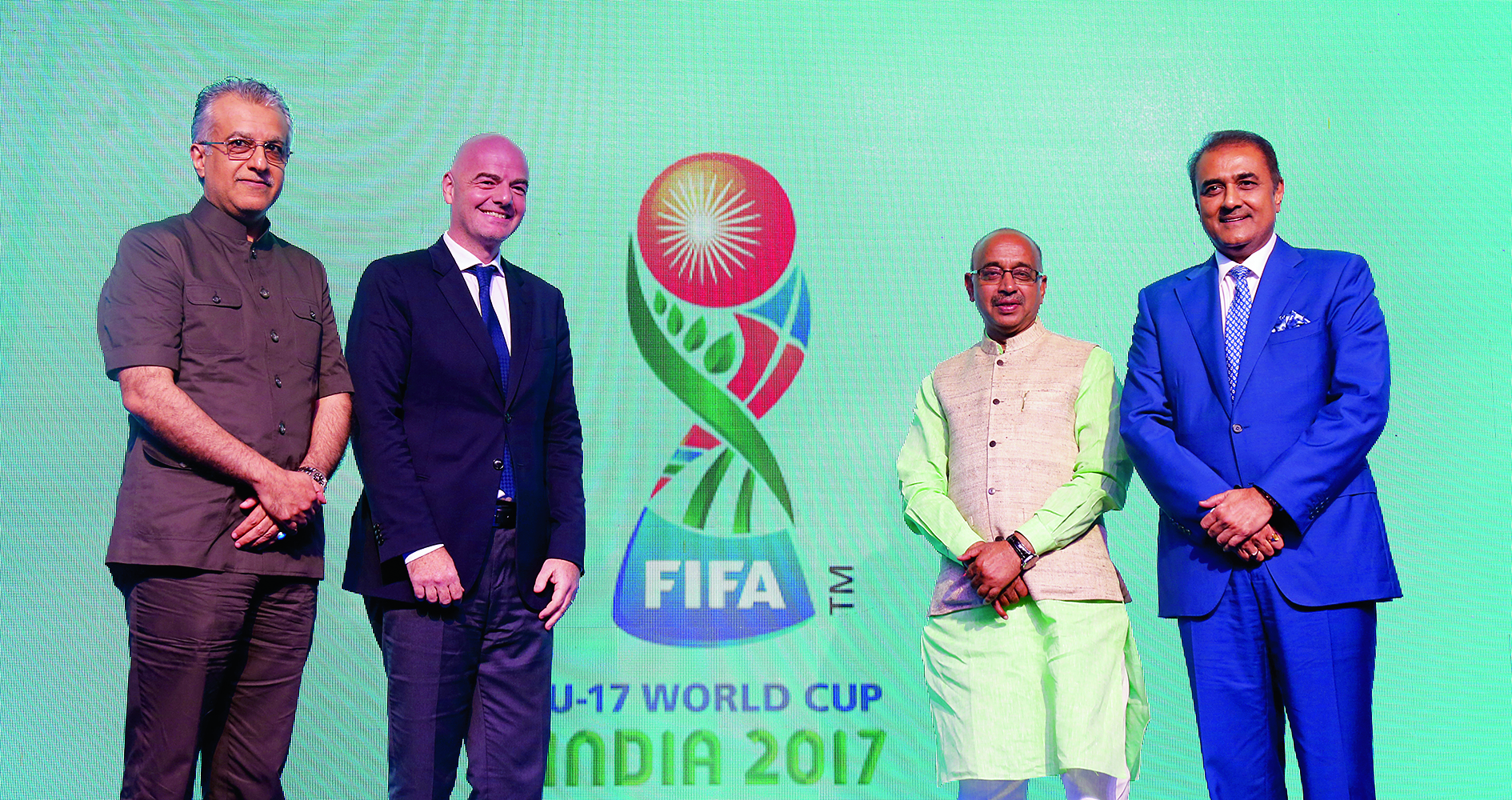

Over the PA star anchor Charu Sharma whipped up the fans. The roaro-meter went crescendo when the cameras of state-run TV Doordarshan panned to Modi, who felicitated a number of Indian football captains. He strode out onto the field, flanked by Praful Patel, the All India Football Federation (AIFF) president and highest football administrator in the country. Fatma Samoura, FIFA’s general-secretary, and Sheikh Salman Bin Ibrahim Al-Khalifa, the Asian Football Confederation (AFC) president, ambled behind. India’s captain Amarjit Singh introduced the PM to the home team.

As the last notes of ‘Jana Gana Mana’ faded into the Delhi night, the atmosphere turned electric. This was a moment the PM and local fans wanted to claim: India’s maiden participation at a World Cup across any age level. A group of 17-year-old celebrities lined up to make history. “This was the best ever prepared U-17 team in international football in terms of training, exposure and financial backing,” said Shaji Prabhakaran, a football consultant and regional FIFA development officer, who watched the game from the stands.

India’s boys simply needed to be seen as competitive with their peers, but a match-up with the United States in the opening game was daunting: this was the last line of American players to come from US Soccer’s residency programme in Bradenton, Florida, which was to close after this tournament. Tim Weah, a Paris Saint-Germain prodigy, and Joshua Sargent, a Werder Bremen prospect, were successors to Landon Donovan, DaMarcus Beasley, Jozy Altidore and Michael Bradley.

Hosts India had not qualified on merit and from the first touch of the game, India-USA was a mismatch. These were boys playing against men. The Americans measured 179.5 cm on average, the Indians 169.5 cm. India were underdogs in the plenitude of the word: small and inexperienced. They lacked the gumption of their counterparts, who were superior in every department of the game. Goliath knocked David out 3-0.

India’s introduction to elite football was brutal. By the full-time whistle Modi had long left. He didn’t want to be associated with a defeat. Indeed, where had the power of Indian youth been during the 90 minutes?

Still, the hosts registered small victories against the United States: goalkeeper Dheeraj Moirangthem’s composure, Komal Thatal’s darting incursions on the right and Anwar Ali’s rasping second-half attempt against the woodwork. These limited, upbeat passages of play were baby steps for a team that struggled to pass its way through the opposition – and summed up the glaring flaw in Indian football: none of these boys had enjoyed organized football at an early age. They were hobbling ten years behind the global standard.

Massive debts

Praful Patel was beaming. On the eve of the U-17 World Cup, he had invited select members of the press, including Times of India, Indian Express and The Hindu, to his guarded residence in Delhi’s Central Secretariat, a high-end hub for politicians and government officials. His invitees were shuffled into a room and drank from a tray of hastily arranged water glasses.

“It’s D-day,” Patel began. He talked up the preparedness of the Indian U-17 team and his plans for a forthcoming centre of excellence. Patel was on a roll. He had been invited by the FIFA Council to sit in on its October session in Kolkata. Patel, a senior AFC vice-president and a member of the FIFA finance committee, could barely contain his joy. In 2019 his AIFF mandate was to end, but here was another chance to pitch India – and himself – to football’s global governing body.

In a corner of the room, an Air India mini-model airplane was a stark reminder of Patel’s murky past. For sixteen years he had served on almost every Parliamentary Consultative Committee on Civil Aviation before becoming Minister of Civil Aviation in 2004. Patel, the reformer of the skies, saddled Air India, the national carrier, with a debt of Rs 160 billion, always threading a fine line between his political and business aspirations. His family wealth had been built in the beedi [cigarettes] business, with the Patels owning a majority stake in the CeeJay Group.

Patel is not a man to contemplate failure. He flaunted his accomplishments, brandishing his success through the prism of India’s next generation in football. In the comfort of his home, he exuded the confidence and smugness that goes with so many seasoned politicians and football officials. Patel showcased how adept he is at dealing with the press, focusing on irrelevant questions and stemming any genuine exchange.

“India never had a programme [like the U-17 team] in the past,” said Patel. “One of the reasons for staging the U-17 World Cup is to refocus on the grassroots and create that awareness and buzz at a much younger age. The grassroots programme is a mandatory licensing requirement for every team, whether in the ISL [Indian Super League] or whether in the I-League. I agree, until a few years back the grassroots programme was very poor. Every player in our U-17 team grew up without playing organised football, except for kickabouts in their village, or whichever way the poor kid could have afforded it.”

“India won the best grassroots program last year, an award by AFC,” stressed Patel.

When Josimar pressed Patel about the non-existent ecosystem between the age of five and thirteen he dismissed the problem with a single word: ‘Lakshya’ or ‘Goal,’ the strategic plan drafted by Dutchman Rob Baan in 2013. The voluminous document is still on the Federation’s website for all to peruse. Lakshya propagates ‘a typical Indian style of play, without copying any other country’, but Baan leaned heavily on ingredients from the Dutch game with build-up play from the back, interchangeable positions and the 4-3-3 formation at the nexus of his proposals.

As master plans often do, Lakshya details with great care a National Youth Development Plan with a National Talent Identification Plan at the core of it, but little of the NYDP or the NTID, if nothing at all, has been realised. Anno 2017 youth football and the grassroots are still chronically stuck in the planning stages. New Delhi is an apt example of the underdevelopment.

At one end of the Delhi football spectrum, football consultant Prabhakaran and his two friends Krishn Anand and Dr Sandeep Kumar, the team doctor of the Indian U-17 team, have invested $500,000 in Delhi United, a second division I-League club. Delhi United has U-18, U-15 and U-13 teams. The club is also in advanced talks with a Bundesliga outfit in order to bring technical expertise and ‘synergy’ to the Indian capital. Prabhakaran, who is a talker, says that ‘it’s a pure community-driven exercise.’ By 2030, he wants to win the Asian Champions League.

The Delhi Dynamos, the local ISL franchise, is a perfect image of the brash Bollywood league they play in. In the past, they signed marquee names Alessandro Del Piero, Florent Malouda and John Arne Riise and appointed Roberto Carlos as coach. Franchises are required to fork out a one-off $2,4 million entrance fee and fulfill a legion of licensing requirements, including compulsory grassroots work. Still, youth development seems to receive mere lip service in a league that is run along commercial lines. The Dynamos organise youth festivals and five-a-side street cups, but do not have a residential academy for their new U-13 and U-18 teams, or the old U-15 team. They signed a technical partnership with the Aspire Academy and gave the Qatari a mandate to set up a proper youth programme. In total, the Delhi franchise will spend 10% of their budget on grassroots work and youth development, up 8% from last season. By general estimation the ratio between first team spending and youth development and grassroots in the ISL is 90% – 10%.

“The physical value of investment is high, considering that ISL franchises don’t make money,” said Ashish Shah, CEO of the Delhi Dynamos. “The current model doesn’t make sense and the club won’t be self-sustaining for long. You need a bottom-up approach. With all our constraints, it takes time.”

“The ISL franchises have got neither the desire nor the incentive,” said Scott O’Donell, the Federation’s former technical director. “Their focus is the first team. They say they are running the grassroots – to a certain extent, but it is not real.”

Back in 2014 the Federation founded the ISL together with their new commercial partner Reliance Industries, owned by the all-powerful Ambani family. They modelled the new league after the Indian Premier League in cricket. The circumstances were unprecedented: the Federation backed a new league at the expense of its own league, the I-League. But then, Patel is so close to the Ambanis that he called the late Dhirubhai Ambani ‘Papa’. This year IMG-Reliance completed a power grab in Dwarka, infiltrating the Federation’s various committees with eight officials. IMG-Reliance CEO Sundar Raman even chairs the technical committee.

In theory, IMG-Reliance can hand-pick India’s head coach.

As an insider, Shah equated IMG-Reliance’s power to ‘certain realities.’

“We [The AIFF] rely on their money,” admitted O’Donell.

“Myelin, Myelin makes perfect”

On the outskirts of Chandigarh, women weed grass next to the dirt road that leads to the entrance of Minerva FC. The sun is dead overhead sector 117, an unprepossessing and poor neighbourhood, just off the Chandigarh Road, a thoroughfare lined with malls, a Subway and a KFC. The sector isn’t part of the original master plan of Le Corbusier’s Indian ‘Ville Radieuse’ – an orderly grid with rectilinear avenues and lush green spaces as ‘the expression of the nation’s faith in the future’ according to India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Here Le Corbusier’s vision of cosmopolitanism, modernism and enlightening through his architectural ideas about light, space and greenery didn’t materialise.

A mural reads ‘Home of the Champions of India.’ That’s an inaccurate assertion: Aizawl FC are the I-League champions. At youth level Minerva’s accomplishments do back up the claim: they won the local State Championship in 2016 and this year they won the U-16 I-League for a second time in a row, a remarkable feat and the fruit of sustained and serious youth development by a delightfully dystopian club on the baking plains of Punjab.

At the club’s premises teenagers mill about. They have come from Manipur, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, New Delhi and South India. A third hail from Punjab. Minerva retains the best boys, who get a full scholarship and free education. They go training, work out in the gym and get hydrotherapy. Minerva’s football academy also has links with the high performance center of Abhinav Bindra, India’s sole individual Olympic gold medallist. The boys sleep in sweaty pre-fab dorms. When it gets too crowded at the hostels of the sprawling fourteen acres residential campus, the army barracks form the back-up plan.

The campus houses an army and a football academy. The military identity prevails as Minerva’s beautification is minimal. The toilet walls are adorned with posters of fighter jets and war ships. Class room quotes – ‘Those who have long enjoyed such privileges as we enjoy forget in time that men have died to win them’ – remind the player pupils of the high stakes.

In 1955 Lt. Col Iqbal Singh Deol founded the military academy. Today his grandson Ranjit Bajaj owns the football club and its academy. The pre-military training school still delivers India’s best cadets, and under Bajaj, who, as a goalkeeper, represented India at the Asian School Games, Minerva has become a football factory. Four Minerva products – central defender Anwar Ali and midfielders Jeakson Singh, Nongdamba Naorem and Mohammad Shahjahan – made India’s U-17 World Cup squad. “My boys,” muses Bajaj. Third goalkeeper Sunny Dhaliwal was the only other non-Minervian to complete the Indian U-17 team roster, plying his trade at Toronto FC.

As the Punjabi sun sets, emitting a golden glow from behind the palm trees Bajaj storms to the academy’s neatly maintained training field, where Minerva, a mix of U-18 players and the senior team, is taking on the Indian Air Force team. They are, like the Indian U-17 team, struggling to pass the ball through the opponent. Players are a touch slow and passes are often overhit. Spanish head coach Juan Herrera, on trial, mumbles ‘mierda’ at so much inaccuracy.

Bajaj is wearing overblown Oakley sunglasses and an overpowering eau de cologne – and he is late. He had missed his flight from the Indian capital, where he witnessed India’s elimination from their home World Cup. The Minerva owner is trimmed and tanned. He is flamboyant, but he is also the young scion son of high-profile bureaucrat parents, father Bharat Raj Bajaj and mother Rupan Deol Bajaj. Controversy is never far away. In the past, he was charged with kidnapping, vehicle lifting, assault and attempt to murder. He is the anti-hero, who revels in his antagonism.

When Jeakson Singh ascended the pantheon of Indian football gods by scoring India’s first – and only – World Cup goal against Colombia, Bajaj was vacationing with his wife in the Maldives. He watched the game on a big screen and began jumping up and down before jumping into the pool. He exulted when he realised that Jeakson had netted the historic header from Sanjeev Stalin’s corner. The goal was a Minerva product. “Anwar Ali and I switched position,” explained Jeakson.

The number 15 moved from the Chandigarh Football Academy (CFA), a government-funded training facility in the city’s sector 42, to Minerva. There, he got a chance to develop in the midfield playing for the senior team and he matured rapidly. “CFA is very good at teaching basic training, but at Minerva I learned how to play in midfield,” said Jeakson. “I improved tactically and technically.”

Jeakson, a gangly and shy teenager, adapted quickly. At Minerva the initiation rites were simple: you’d have to dance the Bhangra and learn galis, the quintessential local cuss words, to become a Punjabi ‘munda [lad].’ Nutrition was also different with a balanced diet and plenty of protein. Butter chicken made away for curry chicken and a little less oil.

He once was a national team reject. In 2015 India’s U-17 coach Nicolai Adam, an International Football Development Advisor at the German Football Association (DFB), with plenty of experience at the Azeri youth level, was alarmed by the teenager’s height: at six feet [180 cm] Jeakson was indeed very tall for a Manipuri. The German coach didn’t want to take any risk in a football landscape where age fraud is rampant. “I was irritated and agitated by Adam, but I am not angry with him,” recalls Jeakson. “My performance wasn’t very good.”

Ultimately, Jeakson made the final squad. In a practice match against the Indian U-17 team, last March in Goa, he convinced Luis Norton de Matos. The Portuguese coach succeeded Adam, who exited India after a player revolt involving claims, counterclaims, conspiracies and concoctions. In his first match de Matos was struggling to communicate with his players. He pressed a ball to implore his players to close down opponents. The reigning I-League champions, who fielded a few older players, ran out 1-0 winners. The result was a shock, the circumstances an indictment for the team’s progression: with a break in their season Minerva were nowhere near match fit. Immediately, de Matos selected nine boys from Minerva.

Even after just 90 minutes de Matos was confronted with a crisis, which questioned how the Federation selected the Indian U-17 team and revealed, again, that youth players had no clear pathway in Indian football. The Federation scouted 14,000 kids around India to assemble the team. At least, that was the official line.

Abhishek Yadav, the Federation’s director of scouting, scanned the leagues and competitions at national and state level. He also set up an online foreign scouting programme together with the Sports Authority of India (SAI). With sixteen players in the final squad the Federation’s academy had a considerable representation. “It wasn’t about helping our [academy] boys,” said Yadav. “It was because we saw them somewhere and thought they were good.”

When Josimar asked Richard Hood, the Federation’s director of youth development, to assess the scouting and selection process behind the Indian U-17 team, he smiled benignly. He was presenting at a football conference at Amity University, which, by Indian standards, was hilarious and slightly diabolical. On stage, Steven Martens’ lack of substance and buzzwords demonstrated why FIFA doesn’t need a technical director. Even the felicitation ceremony was awkward.

Hood kept a low profile. His small frame conceals a gentle soul. He is soft-spoken and very knowledgeable. Hood is Patel’s anti-thesis and the first to admit that the scouting didn’t proceed along professional lines where multiple opinions and repeated evaluations over a prolonged period eventually result in a carefully weighed decision about a player.

“It [the scouting] was a shot in the dark,” explained Hood. “It had to be done, but the process exposed us. India doesn’t have a youth or league structure that is propping up the players. Go look at West Bengal’s U-18 league which runs for a couple of months – this boy is there. Watch the right-back in the Manipur U-18 league. Check out the centre forward in the Mizoram U-13 league, he is special.”

The Indian U-17 team was sent on a crash course of exposure tours. They rushed to fifteen countries, including Brazil, Mexico, Germany, Norway and Iran. The Federation spent $2.5 million on the team’s preparation, copying the United Arab Emirates’ model from the 2013 U-17 World Cup. The Gulf hosts were eliminated from their own party in the group stages suffering three defeats and a goal difference of -8.

For India, the outcome was frighteningly similar. The hosts finished bottom of the 24 participating teams. Even World Cup debutants New Caledonia, with a population of 278,000, drew 1-1 with Japan. In the final group game Ghana demonstrated why the U-17 World Cup had for so long been the natural preserve of African teams. The Black Starlets were physical, skilful and ruthless in deconstructing the pragmatic philosophy of de Matos, who had gradually moved away from Adam’s expansive experiments. Still, fourteen of the German’s picks had made the final 21-man squad.

The Ghanians had begun playing football at the age of four and India were relegated to a jejune support cast, the result of a chronic disregard for grassroots and youth development. The U-17 World Cup should have been a great launchpad for the development of Indian youth football, but instead became a vanity project for local administrators, with top-heavy beautification, stockpiling teenagers in Bollywood style. At nursery level the neglect remained.

“It was probably the most expensive preparation period in the history of a national junior team,” said Hood. “It reflects how fragile the Indian youth system is – that we can’t have the clubs and the ecosystem bring in the players for us.”

Back in Chandigarh, Bajaj, for all his eccentricities – his mother ‘Queen Ficus’ owns India’s largest bonsai collection, which stands scattered around the academy – and hyperbole, offered a thoughtful, scientific explanation for India’s compounded World Cup misery: the disregard for the protein Myelin, the insulation that wraps around the nerve fibbers in young brains and increases signal strength, speed, and accuracy. Myelin responds to repetition by wrapping new layers around the nerve fibbers and that allows a football pupil to process the required skill faster, up to a 100 times – or in a Hood tagline ‘Practice makes Myelin, Myelin makes perfect.’

Football is the art of learning a language. The window for ‘deep practice,’ the contested threshold of 10,000 hours of practice over ten years that will allow a talent to attain the elite level, shuts down at thirteen or fourteen years of age. Indian players don’t grok football at a profound level. They have not passed the ball a 1,000 times at the age of seven. At fourteen, it’s too late: that quick, natural connection can’t be nurtured anymore. They lack mastery, creativity and competitive aggression.

Next season, Bajaj wants to introduce football at the U-9 and U-7 level at Minerva. “It is not enough,” lamented Bajaj. “What is one club in one bloody city in the north of India going to do?”

Do the Royte thing

‘Thy Kingdom Come’ reads a sign at Aizawl’s mini-airport and terminal building. It’s a long and winding road from Lengpui to India’s footballing kingdom, carving its way through a thick tropical forest of Bûng and Fâes trees and past a remote Presbyterian congregation, weaving a neat trail across Mizoram’s topography into the city, where steeply built houses hog and cling onto the dozens of hills that form Aizawl, a heartland of Indian football.

Once in Bawngkawn, one of the city’s municipalities, jeeps and scooters come to a standstill. Even Aizawl is no stranger to traffic gridlock with stray dogs napping on the roadside. It’s a miniature version of India and yet Mizoram and the Northeast don’t belong to the subcontinent’s mainstream.

The Northeast is a rich tapestry of cultures, tribes, religions and languages. The contiguous Seven Sister States and Sikkim, at the foothills of the Himalayas, are a tumultuous hodgepodge of ethnicities and creeds: Bodo, Kokborok, Garo, Mizo, Kuki, Metei, Monsang, Tangkhul, Zeme Naga… Buddhist, Christian, Baptist, Donyi-Polo, Hindu, Animism… Historically, the region has been marginalised. Plenty of flatlanders want to slit the chicken’s neck and banish the hill folk.

School is out in Aizawl and at the government-owned Chite ground, kids, aged eleven, twelve and thirteen, line up. Their small-framed bodies freeze as they face Bengali coach Jahar Das and his walrus moustache. Suddenly they rattle off a number – 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. The little drill must reboot the players’ mindset before practice. They can’t zone out during the next 90 minutes. The boys spread out. The clatter of their cleats is obtuse and the ball ricochets of the field, which, after torrential rainfall during Diwali, is bone dry and, in patches, muddy.

On the surrounding Lushai hills the sun lingers and a cool breeze gently rustles in the trees. Das splits up the group: the U-13 players work out with physical exercises as the club’s youngest members hone their skills zigzagging between white and yellow cones. They will continue with individual drills – feint left, feint right and dribble. The big boys play a match on a reduced field with sticks as uprights. The rule is very simple: whoever wins or excels in keepie-up gets sartorial privilege. The others must take off their shirt. The half-naked boys reveal a frail pint-sized build, hiding the advent of puberty. Still, they control the ball expertly, display nifty dribbles and radiate a confident understanding of the game.

Das is prepping the boys for the inaugural U-13 I-League season.

In June, Aizawl advertised a call for trials in Mizoram’s vernacular newspapers and 132 boys flocked to the Chite ground to parade their skills. They were whittled down to a select 30. “Game freedom is what matters,” said Das. “We may lose in the [U-13] I-League, but development requires time.”

The Kolkata coach was the first Indian to obtain an AFC A-licence and is the de facto head of youth development at Aizawl, supervising the club’s grassroots activities in Mizoram and its outer corners, Tripura and even Myanmar. Das drafted the curriculum but has been moved down the development chain to instruct the youngest Mizos. Back in the 80’s Das traveled to Bonn and Hennef where the tutorials of Holger Osieck, West-Germany’s national youth coach, influenced him profoundly. He deepened his knowledge about the enhancement of physical conditioning, the refinement of fast and accurate passing and mental coaching. Those three takeaways have remained the cornerstones of his methodology and Das has applied it across all age groups.

His supervision is somewhat lax and old-fashioned, a complaint among the Aizawl hierarchy. At the end of the session a boy screeches in agony after a bad tackle. Das rushes to tend to him with a handkerchief and splints. In haste the boy is wheeled off to hospital.

That night the general-secretary of the Mizoram Football Association (MFA) Lalnghinglova Hmar – Tetea – attends the Mizoram Premier League (MPL) match at the Lammual Stadium between Dinthar FC and Chhinga Veng FC, the league leaders of the semi-pro competition. Tetea, smartly dressed in black, is credited with revolutionising Mizoram football: the MPL is a development platform for local players. His brainchild has been a huge success, even without major sponsors or international brands backing the league. Globalisation hasn’t penetrated the region yet and last season Mizoram, with one million inhabitants, provided more than 50 players for the I-League.

Yet Tetea admits that Mizoram’s success is down to the shortcomings of India’s other state associations. Even Mizos don’t have a steadfast player pathway. Below the U-18 MPL youth football is an unsorted mix of school sports, village games, local tournaments, Subroto Cup ventures and camps. This season the MFA will introduce baby leagues – U-12, U-10, U-8 – in Champhai, a district on the Indo-Myanmar border, to complement its existing grassroots program. “In two to three years we may have a clear pathway, but we must understand the strength and depth of our league first,” said Tetea. “The MFA can’t do it alone.”

Robert Royte’s house floats in the sky. In Aizawl every level is connected. The morning mist is fading fast, but drifting clouds prolong the shroud of white haze over the hills and the city. In the distance the Lammual Stadium and the beautifully carved-out ‘Tlang’ [mountain] stand canvas the landscape. Aizawl’s U-18 team is practicing at the ground. The emphasis is on quick pivots in the midfield. U-18 coach Rohmingthanga Fanai, a novice in the trade, demands one-touch passing, but his players – the majority began playing organised football after the age of fourteen – aren’t listening.

This morning two boys from the remote village of Sialsuk ran trial. They, like the others, have carved out a pathway in their mind: from the U-18 MPL to the elite MPL, a road that may lead to other I-League clubs or ISL franchises. “The level of development varies in my group,” said Fanai. “[They] began playing too late. Their skills and technique are good but physically they are not mature yet. We don’t have a gym. We do push-ups and sit-ups. [In the future], the MFA grassroots programme will help.”

Royte, the club’s chairman, is a Mizo native. He heads Northeast Consultancy Services (NECS) which offers expertise in software design and civil construction. The bulky and square-framed Royte talks incessantly on the phone and chuckles at the sight of his own cartoon next to his giant flatscreen TV. A local cartoonist has depicted him with a cross and a football, sketching the local entrepreneur as Aizawl’s messiah.

In a way, Royte is. He rejuvenated a defunct club, steeped in history and schmaltz, and last season led Aizawl to the I-League championship, a sterling renaissance for an outfit on the brink of implosion. He likes to think that his youth department played a pivotal role in Aizawl’s dreamy ascension. “Catch em young,” quipped Royte. “I wanted to professionalize the game, but also detect talent at an early age. Our experience teaches us that we want to identify talent at the age of fifteen.”

Next year Royte wants to modernise his club with a state-of-the-art residential academy in the minute village of Lungleng, fifteen kilometres from the state capital on a road lined with bamboo and bitter bean plants. The training field sits top of a mini-plateau, next to a cubicle building that will incorporate all the modern amenities of a manicured European academy. It’s an oasis, but for the locusts’ spine-tingling clangour. Here, Aizawl wants to produce the next Lalengmawia, Mizoram’s sole player in the Indian U-17 team. “Mizoram has contributed players across India’s age groups,” pondered Royte. “Why did Manipur get eight?”

Back in the city, Royte watched Aizawl FC – Bethlehem Vengthlang FC. In the stands everyone chewed paan [betel leaf nut]. Winger Rochharzela was the only home-grown player for the hosts. Aizawl FC ran out comfortable 5-1 winners. As soon as the players disappeared into the dressing rooms and the floodlights dimmed, the Lammual Stadium turned into a playground for kids chasing footballs and their dreams.

Underdeveloped, fragmented and disorganised

In Kolkata, West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee received FIFA president Gianni Infantino as a head of state. All over the city, the ‘Biswa Bangla’ brand posted ‘Bengal, the game is on.’

On the morning of the World Cup final, East Bengal’s U-18 team play an informal game in the shadow of Eden Gardens, the iconic spaceship-like home of Indian cricket. From the decrypt, concrete bleachers U-18 youth coach Ranjan Chowdhury watches on. From the 22 boys on the pitch, eight were Manipuri.

Chowdhury is a respected, but divisive coach. He masterminded the success of the Tata Football Academy, India’s supply line of youth players in the 90’s, but, among seasoned observers of the Indian game, Chowdhury is considered ‘the king of age fraud.’ The Bengali coach, like his colleague Das in Aizawl, has a German connection: he studied at the Sport University Cologne to get his coaching licenses. Chowdhury was a pioneer in reaching out to players from the Northeast, whom he refers to as ‘Mongolians.’

In his hometown Kolkata and West Bengal at large nursery football was never structured. East Bengal and Mohun Bagan simply cherry-picked players from the approximately 160 clubs in Kolkata’s metropolitan area. The legacy clubs did little to advance youth development, always broaching ‘heritage’ as an apology for their inertia. Even today the city’s big two shun modernisation, but in an ISL-world they are woebegone anachronisms. This season East Bengal will have to field an U-13 team for the I-League to face Royte’s and Bajaj’s youngsters. The club selected players within a 20 kilometre radius around Kolkata.

“Since a year or two, East Bengal is giving more importance to youth development and grassroots programs,” said Chowdhury. That evening he attended the World Cup final. England’s wonder kids dazzled in a sumptuous 90 minutes of high-octane, modern junior football. Philip Foden, the player of the tournament, and Rhian Brewster, the Golden Boot, were exponents of a rich football tradition that, at different levels, redefined its grassroots and youth programs after much needed introspection. They were lightyears ahead of India, whose football establishment still floated the idea that this tournament was a seminal moment for the domestic game.

Amid all the euphoria and self-gratification, Patel pitched for the 2019 U-20 World Cup. The Delhi High Court however removed the football autocrat from the Federation’s presidency over elections irregularities. The U-17 World Cup was a short-term sophism: at grassroots level, the Indian game remains deeply underdeveloped, fragmented and disorganised. In 270 minutes of football twenty-one teenagers could not possibly change that.