For years Noël Le Graët, president of the French Football Federation, and other senior officials at the federation have been covering up multiple cases of sexual abuse, including abuse of underage players.

By Romain Molina

Noël Le Graët (81), the octogenerian president of the French FA, the FFF, has decided to sue French magazine So Foot for libel after it had published detailed allegations of sexual misconduct against him, allegations which were widely reported in France’s media.

So Foot published several text messages that Le Graët had sent to employees of the FFF, which included:

«Come to my place for dinner tonight.»

«I prefer blondes, so if you’re up to…»

«You’re quite pulpy, I would definitely put you in my bed.»

But his case is not isolated. It is in fact, as Josimar has found, only the latest in a long series of lurid allegations of sexual abuse and harassment within the FFF, many of which involve children, which the French FA has systematically tried to suppress.

“When something happens, you keep your mouth shut. That’s how it works.” A former board member of the FFF agreed to speak to Josimar on condition of anonymity. “Otherwise, I’m done. They’re too powerful. The second you speak about the abuse, you’re out of the game. It’s not only the FFF but also the LFP (professional football league), the clubs. I mean, did you see how many cases we have been facing in the last couple of years? What did we do to protect our kids?»

There have been several cases of sexual abuse, blackmail and harrassment, also towards underage players (boys and girls) involving coaches, scouts, agents and senior officials working in France’s top flight. PSG, Lyon and Troyes are among the many Ligue 1 teams which have suppressed these issues without taking any proper action. The same happened at the FFF. The French FA chose to remain silent, keeping the information away from the country’s highest authorities. “They never spoke to me, to us, about it”, says Thierry Rey, the sports adviser to the then president, François Hollande. “Neither [did they speak to] the sports minister. The gravity of the facts should have been taken very seriously.”

The FFF president Noël Le Graët admitted in a internal document seen by Josimar that cases of sexual abuse involving underage players took place at its national training facility, Clairefontaine.

Still in the game

Since the mid-1980s, the FFF has received multiple complaints of sexual abuse, harassment and inappropriate behaviour towards underage boys and girls. Although some individuals were removed from their posts after investigations into the complaints, two of these individuals were allowed to keep their coaching licences and continue their careers as if nothing had happened.

The first is Angélique Roujas, a former French international player with 51 caps and the coach in charge of the women’s section at the national training centre at Clairefontaine, was sacked in 2013 after the FFF had learned that she had had sexual relations with underage players. Yet she continues to work with young female players in France. After serving as general manager of FC Metz’s women team (where she worked with girls aged 6 to 13) between 2014 and 2019, she took over the U19 women’s team at Ligue 2 club ESOF La Roche, where she still works today.

The second is David San José, who was fired by the FFF in 2020 over inappropriate behaviour towards a 13-year-old at Clairefontaine, but has also continued to work with young players at Olympique de Valence.

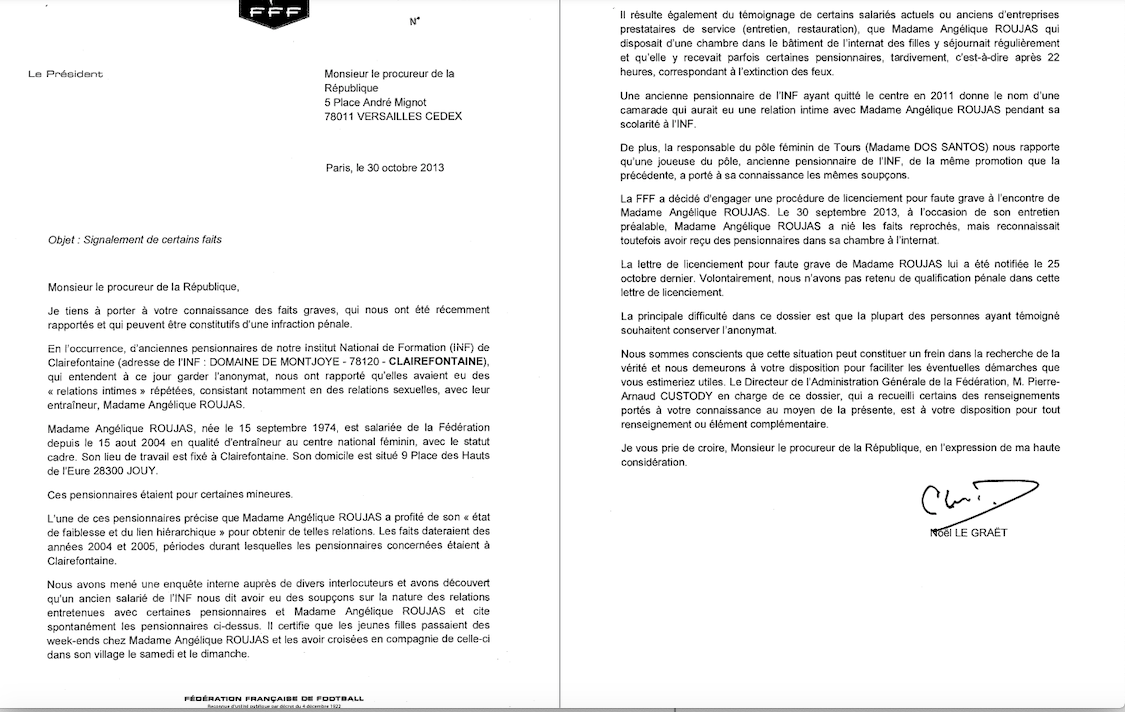

In the internal document dated 30 October 2013, FA president Noël Le Graët wrote:

“One boarder mentioned that Madame Angélique Roujas took advantage of her state of weakness and her hierarchical link to obtain such relations (intimate ones). The facts went back from 2004 and 2005, a period in which the concerned boarders were in Clairefontaine.

We started an internal investigation with several interlocutors and we discovered that a former INF (Clairefontaine) employee told us he already has suspicion on the nature of the relations maintained by some boarders and Madame Angélique Roujas.(…). He certified that young girls spend their weekends at Madame Angélique Roujas’ home.

One former boarder at Clairefontaine who left in 2011 gave the name of a teammate who would have an intimate relationship with Madame Angélique Roujas during her scholarship at Clairefontaine.

Besides, the head of the women academy in Tours, Madame Dos Santos, told us that a player, also a former boarder at Clairefontaine, from the same generation as the girl we just mentioned, brought to her attention the same suspicions.

On 30 september 2013, during her preliminary interview, Madame Angélique Roujas denied the allegations but nevertheless admitted having received boarders in her room at the boarding school. Willingly, we have not retained any criminal qualification in this letter of dismissal. The main difficulty in this file is that most of the people who testified wish to remain anonymous.”

“They did nothing”

The FFF says all coaches are subjected to a “systematic check of their integrity” before being granted a licence, and that any criminal convictions would prevent it from being renewed. Nevertheless, the federation has been accused of failing to take appropriate action when dealing with allegations of sexual aggression and harassement, notably at its prestigious Clairefontaine academy.

Two former FFF employees have also claimed that they raised concerns about the federation’s handling of the allegations, only to be told not to talk about them by Brigitte Henriques, a senior FFF figure from 2011 to 2021 who is now the president of CNOSF, the French Olympic Committee.

François Blaquart, the FFF technical director from 2011-17, who sacked Roujas and San José, said this to Josimar: “I removed these people immediately. Beyond that, I don’t know what the FFF did, it’s not my job.”

In 2014, the women’s section moved from Clairefontaine to Insep, the national institute of sports, on the outskirts of Paris. “It was for logistical reasons”, says Blaquart. “That was the main reason but also because we needed to handle the problems, it’s true.”

A former international tells Josimar she was a victim of Angélique Roujas, She does not want to be named. “I was a victim at Clairefontaine – I know what happened and I know how hard it was to rebuild myself. Even today, I don’t want to talk publicly about it because it’s painful and I’m not sure that I will be supported. I told some senior people inside the federation, including Brigitte Henriques, the vice-president at the time, but what happened? Nothing. They did nothing.”

Melissa Plaza, who retired from football in 2013 after winning two senior France caps, claims that she felt threatened professionally by individuals at the FFF when she raised allegations of abuse and harassment in an interview with L’Équipe last October after the release of her 2019 book, Pas pour les filles?

“It’s a widespread issue because it’s happening at club level as well”, she says. “But no one is talking freely. If you do, you can say goodbye to your career and all the sacrifices you’ve made over all these years.”

Another former director of the FFF told Josimar that “the fédération is like a hairdresser’s salon – everyone talks to everyone. They all know about these cases, but they get buried very quickly. It’s a policy of silence. They are like ostriches with their heads in the sand. If you talk, you are out.”

Josimar has looked at a number of cases which have left the FFF with questions to answer.

Angélique Roujas

The one involving Roujas is still causing particular concern inside the FFF and French women’s football. On 25 October 2013, Roujas was dismissed without compensation as the head of women’s football at Clairefontaine – the world-famous centre established in 1988 in the heart of the Rambouillet forest – after being found to have had sexual relations with underage players.

Five days later, Noël Le Graët, the president of the FFF, wrote to the local prosecutor, as he must do by law, being a civil servant. “He was pressured to do it because the national team players threatened to strike”, a star player at the time tells Josimar.

“We threatened the FFF with refusal to play if she was allowed to be part of the coaching staff of the national team. That’s why they made the decision after almost a decade of inaction.”

In his official letter Le Graët detailed the accusations made against Roujas, that she had sexual relations with underage girls in 2004 and 2005, providing an example from a former boarder who claimed Roujas “took advantage of her state of weakness and her hierarchical link” to have relations with her. “The FFF has decided to initiate a dismissal procedure for serious misconduct against Mrs Angélique Roujas”, Le Graët stated.

According to four government officials at the time, including the then state secretary for sports Thierry Braillard and sports minister Valérie Fourneyron, no effort was made to make them aware of the case, although it was required by French law. Najat Vallaud-Belkacem, the former minister of national education, women’s rights, youth and sports, told Josimar that “this topic never came to me. The FFF had the obligation to report it [to me] but they never did,”

The police investigated allegations made by one former international from 2004, but after almost two years the case was closed because the allegations were judged to have passed the statute of limitations. By then, Roujas was working at Metz, and, according to sources, more people had complained to the FFF about Roujas’s behaviour at Clairefontaine.

“Brigitte Henriques basically told me to shut up”, remembers a former senior member of the FFF. “Henriques was vice-president of the federation. She was very clear about Angélique Roujas. We didn’t speak about it.”

Two other employees have claimed that Henriques told them to remain silent. “She was in charge of women’s football and didn’t move a single finger to help the girls”, says a former security guard who worked at Clairefontaine.

According to documents seen by Josimar, a former France international said she “asked [Henriques] how the federation could let Angélique take a job at Metz. She told me that an investigation was ongoing and since it wasn’t over, the federation couldn’t do anything.”

According to article 85, section five of the FFF’s general rules, the federation could have taken action against Roujas, who was dismissed after it was was claimed that she took advantage of “the weakness” of underage players in order to have sexual relations with them. “The refusal to issue a licence, or its withdrawal, could also be applied for the same offences (against morality, honesty or honour) even if they are not subject to a penal sanction”, state the FFF regulations.

Roujas has consistently denied the allegations. “I absolutely dispute the assertion that I allegedly shared the same bed with a minor”, she wrote in response to an article in L’Équipe in 2019. Roujas is now in charge of the youth section at her former club La-Roche-sur-Yon.

David San José

San José was responsible for organising non-football education at Clairefontaine and was fired for inappropriate behaviour after sending love messages to a 13-year-old player at the centre in 2013. “Je t’aime mon bell”, he wrote in dozens of messages seen by the entire team.

He insisted that the boys’ weigh-ins was done without underwear,

Nevertheless, he continued to work in football and obtained his Uefa A licence five years later, supported by a certificate signed by Le Graët.

“How am I supposed to know he was fired for his behaviour at Clairefontaine ?” asks Malik Vivant, the general manager of Olympique de Valence who went to hire San José. “The FFF didn’t tell anyone. So how can the clubs know ?”

Again, the FFF could have used article 85 of its statutes to prevent San José from keeping his licence. Dozens of players told Josimar that the FFF “hid what happened” and “never made any internal investigation”. A roommate of the alleged victim, Hedi Mehnaoui, told Josimar that “no one asked him anything […] If the FFF is saying now they investigated, they are lying”. According to the article 40 of the French penal code, it was the duty of FFF to report those allegations. “They didn’t do it”, remembers the sports minister at the time, Valérie Fourneyron.

The New York Times and L’Equipe reported other inappropriate behaviours towards underage boys after he left Clairefontaine.

Élisabeth Loisel

Loisel, a former defender who won 40 caps for France, was coach of the national women’s team for a decade. She stayed at the FFF after leaving that post in 2006, helping young coaches to obtain their licences, She remains a Fifa instructor.

Two former players say that in 2001 they complained that Loisel was forcing players to have sex with her in order to be selected for the national team. Josimar understands that similar complaints were made to the FFF in 2004 and 2006 but never investigated. “I told my players that they can go to Clairefontaine but if they wanted to go there’ll be some risks”, says a former president of a women’s club, who did not want to be named, to Josimar.

According to several senior officials, the FFF president, Noël Le Graët, questioned Loisel’s suitability to take on a job with a youth national team. “Well, we can’t really let her coach kids… “, he said during a meeting. Nevertheless, she stayed in position.

Gérard Prêcheur, the former director of the women’s section at Clairefontaine who worked with Loisel, also accused her of selecting players on the basis of their sexual orientation during his interview with the police who was investigating the Roujas case. “In 2004, I expressed the wish to leave. I had two divergences of approach with Élisabeth Loisel, the national team manager. Firstly, I favoured the technical aspect and she favoured the athletic one. Secondly, I realised she favoured also some players because of their |homosexual] sexual orientation.”

Marc Varin

In October 2021, the FFF was found by a French court (les prud’hommes) to have ignored its “security obligations” towards an employee who was a victim of sexual harassment. The employment tribunal judged against the financial director, Marc Varin, but sources claim that inside the FFF he had been treated “like a victim and a hero” in the weeks before the verdict.

During a meeting of the executive committee, Varin was presented as a “very brave man who suffered with his family. It’s terrible what they’ve done to him. He’s an amazing person”. Many people were scandalised by the way the FFF treated the victim and the people who testified in her favour. Isolated and pressured, at least four employees left the federation.

“We have to ask ourselves something: Is it normal that so many cases happen inside our federation?”, the former FFF director says to Josimar.

Gaëlle Dumas

In May, the former France youth coach Gaëlle Dumas left her post after complaints of harassment made against her by underage girls at the Blagnac centre of excellence which is owned by FFF. The complaints were first sent to the administration in charge of the protection of children in the département of Haute-Garonne.

According to the Tribunal de grande instance (Regional Court) of Toulouse, Dumas has been charged with “abuse of authority and violence over minors”. She will face trial in November.

Other cases

Josimar’s investigation has also raised questions about other cases. They include allegations that former France women’s coach Francis-Pierre Coché was sacked for sexual blackmail and harassment in the 1980s. The FFF has never publicly communicated its decision.

Sources have also claimed the FFF has failed to investigate allegations of moral and sexual harassment against Yves Ethève, who has been the president of la Ligue de la Réunion for almost 40 years and is currently facing a criminal trial.

Jacky Fortepaule, the former president of la Ligue du Centre, was found guilty and received a one year suspended jail sentence for sexual and moral harassment. During the trial, the victims spoke openly about the inaction of the FFF.

In August, Daniel Galletti, the president of the refereeing regional commission of the league of Paris-Ile de France, was forced to quit his position after his bosses confronted him with proof of sexual blackmail and harassment. Galletti was also involved with the FFF as a “referee observer”. Yet, again, the FFF didn’t say a word – just like they remained silent when a physio had sexual relations with a 16 year-old girl he treated in Clairefontaine, according to police documents seen by Josimar.

Josimar has also received emails from several families and coaches asking for help to the FFF about sexual abuse happening inside their own club. In each case, the persons involved told Josimar they didn’t receive assistance or sometimes even an answer.

All the politicians mentioned (former sports minister Najat Vallaud-Belkacem and Valérie Fourneyron, former state secretary for sports Thierry Braillard, and former sports advisor to the then president, Thierry Rey and Nathalie Iannetta) confirmed to Josimar they weren’t alerted for any of these cases.

The FFF, Brigitte Henriques and the league of Paris-Ile de France didn’t answer our questions.

According to the French Law, article 434-1, 434-3 and 434-4, not informing the authorities when you are aware of a crime could be sanctioned of three years of jail and a 45 000 euro fine.

If you have any information about sexual abuse in football, contact romainmolina@protonmail.com.